“After a time, you may find that ‘having’ is not so pleasing a thing after all as ‘wanting.’ It is not logical, but it is often true.” —Mr. Spock

Buying a building is not quite like pon farr, the Vulcan mating ritual from TOS episode Amok Time, but it’s close in the sense that it can make you go crazy.

Helen didn’t take as much convincing as I expected. When driving by the building with her friend Lise, I later learned that she commented, “Rob is going to want that building.” But there were significant obstacles.

First, we had to be sure the asking price of the building was realistic. Two appraisals showed that the $ 1.4 million sales price was almost twice the building’s value. We countered with a non-negotiable offer of half that amount. As expected, the seller refused, and we dejectedly resigned to keep looking. Sometimes, as much as you want something, you must walk away because the having just won’t work. To our surprise, within a week, he called back and accepted our offer. Later we found out that if he didn’t sell quickly, he would owe a huge tax penalty.

Second, we had to sell the Kalorama studio to buy the new property. Reputable agents in the Adams Morgan area dismissed the possibility of a quick, profitable sale and refused to help us. We had designed our studio to be an ideal casual workplace, and I felt confident a buyer would agree. So, we put the townhouse up for sale ourselves, and the first people to tour the space bought it.

Third, although the county and state offered loans, it wasn’t enough, and we needed to finance the remainder. Our long-time bank was too small to make the loan, but they convinced another to make the deal. The roller-coaster ride of building our new studio was about to start.

We hired a construction firm to gut the building interior and haul away the debris to begin the renovation. Before they came, we decided to throw a “graffiti party” to inaugurate the process, allowing our 7- and 10-year-old kids, Steven and Rebecca, and their friends to paint and draw on the walls and floors throughout the empty retail space. Who doesn’t like the idea of committing legal defacement of property—plus pizza? At first, they used chalk on the floors and paint on the walls, but soon it devolved into a Lord of the Flies event. Kids started painting other kids, splashing them with buckets of tempera paint, and using them as human paintbrushes along the walls. No one was hurt, and the interior looked like a grunge art exhibit.

Working with our architects, Howard Goldstein and Jill Schick, we had decided to create a studio space on the third floor emulating an industrial loft with the requisite exposed brick walls, open ducts, and light fixtures. We worked up some preliminary plans, but first, we had to demolish and remove the existing interior space all the way to the brick walls and trusses—removing a cheap 1984 renovation of small rooms, threadbare wall-to-wall carpet, and low suspension ceilings completed after the Masons sold the building.

The ground-level floor began as a Nash auto dealership with gas pumps by the front door. Still, over the years, it had been a furniture store, a Chinese restaurant, and eventually broken into several spaces that at various times included a tuxedo rental shop, a coin store, and a phone parts store. Demolishing the retail space to the dirt and beams revealed interesting artifacts. The demo crew opened a section completely closed up in the seventies—the back room of the tuxedo rental shop complete with posters, sample books, furniture, supply cabinets, and a calendar on the pine-paneled walls forever halfway through 1974. It was not quite King Tut’s tomb, but entering the space felt like a trip back in time, as if the owner had just stepped out.

Even more astounding was finding another walled-up section that contained the building’s original air conditioning system. A giant Rheem compressor and blower the length of a bus might have been the first office air-conditioning system installed in Silver Spring.

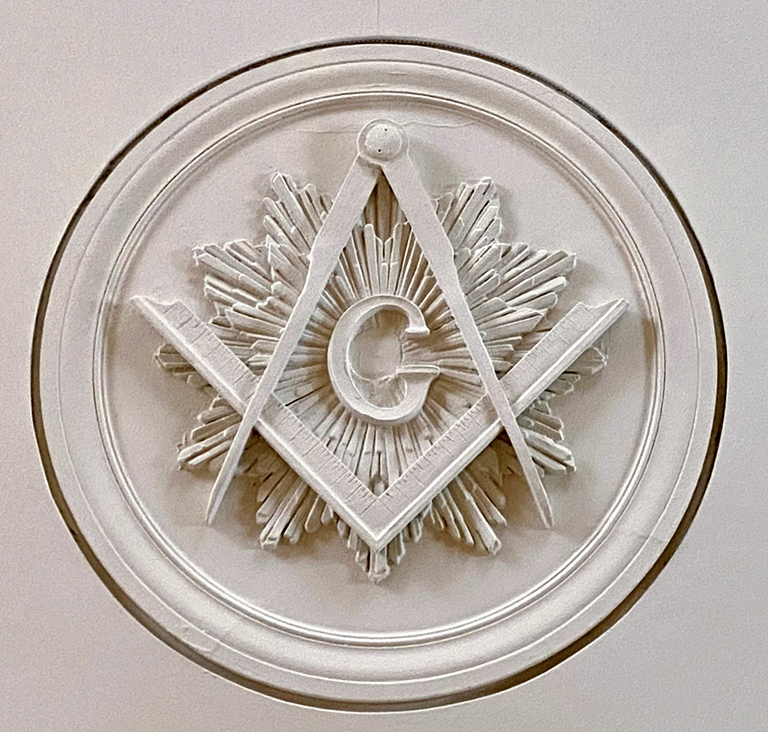

The top floor—what would become our studio—had more surprises. We weren’t sure what was in the space above the eight-foot suspended ceilings, but we knew that each floor was 15 feet high. We were watching when the demo team came to clear out the space. They started with the drop ceilings, and, after a dead pigeon tumbled out, we quickly discovered that the original interior of the third-floor space was still there—the ’84 construction had been built inside it. The actual ceilings appeared ornamented with gold-leaf egg-and-dart moldings above rows of rosettes. Soffits encasing the outer-wall steel girders were designed as large Greek Ionic columns. The middle of the ceiling had a five-foot circular Masonic seal with a curious hole drilled in the center. The large space echoed the Greek Revival style of the building’s exterior. Pulling up the carpets revealed original maple flooring was still in excellent condition. It was entirely usable, albeit antiqued by decades of wear, but that only gave it more character.

These discoveries immediately canceled our faux-loft concept, and we decided to restore the space as much as we could to the days when it was the Masons’ Ceremonial Hall. Wanting an industrial loft-style is excellent, but already having an attractive design is better. The contractor hired restoration experts that worked on the U.S. Capitol to make molds of the plaster ornamentation to replace those that deteriorated or had been removed. We even rebuilt some clerestory windows that bricked up when the original AC was installed.

In the end, we did add modern lighting and ceiling fans and abandoned the flashy gold leaf on the moldings, but the space looked like its original self. As for the mysterious hole in the Masonic seal? Above the seal in the attic, two spotlights could light up a glass rod that poked through the hole, sending a beam down to the floor below. What strange Masonic rituals were conducted? We don’t know.

We had to move out of the Kalorama studio months before the renovation would be finished, so we rented temporary quarters in the office building next door. From our fourth-floor windows, we could watch the construction. That came in handy when we noticed the HVAC crew attempting to install one of the rooftop units in the wrong place. They were looking at the blueprint upside down.

We replaced and upgraded all the electrical, plumbing, and HVAC systems. A new transformer and power line were added in the alley behind the building and routed underground to the basement. Unfortunately, the PEPCO crew did not waterproof the conduit properly. During the first downpour after completion, the water poured into the basement as if a large pipe had burst. From the lobby above, it sounded like a waterfall.

One aspect of the original building that stood the test of time was the exterior brick walls. One part of the renovation called for relocating the front door to create a modern lobby. But Masons had built the building, and the wall, with its 1927 mortar formula, proved a challenge to demolish. After an hour of unsuccessful flailing with a pickaxe, the construction worker returned after lunch with a jackhammer. Multiple attempts did not yield a brick. The next day, a backhoe pulled up next to the wall and jackhammered away, finally carving out a section where we would install new entrance doors. But the large piece of disembodied wall needed even more pounding before it would give up individual bricks.

The initial build-out included the lobby, stairway, and third-floor studio space. We built out the rest of the building next year, including a large conference room/photo studio on the second floor. Wanting to rent the rest of the building is not the same as having a tenant who will use your designs.

We could do this because we had found the ideal tenant—the Silver Spring Regional Center, created to help revive downtown Silver Spring. It was no surprise that they wanted to rent two floors of our building, a prominent historic landmark at the edge of the downtown special business district because they worked hard to help us buy it. What better tenant to have than Montgomery County? No issues with permitting, no financial problems with our lenders. And, because the first floor was to house the Silver Spring Urban District, responsible for maintenance in the area, they had a keen interest in making The AURAS Building, as we named it, look great.

We moved into the building on July 1, 1998, and had an opening ceremony the following week. Although we can’t claim credit for reviving downtown Silver Spring, the CEO and President of Discovery chose our unfinished first floor to announce they were moving across the street and planning a large complex to house their growing media empire.

For the last twenty-four years, we’ve happily worked in our third-floor space, and unlike the advice from Mr. Spock, the having has been much more fulfilling than the wanting of it, logical or not.